Our ‘International Dialogues’ hosts socioeconomic rights expert Christopher Mbazira

Are a constitution and a constitutional court capable of effecting social transformation? These are some of the questions our next guest will be addressing.

We are back this week with the

Aside from sitting in one of the most influential constitutional courts in Latin America, Carlos Bernal, a leading scholar in constitutional law, is the author of several books and has published in the some of the world’s most important journals.

Few topics are as controversial in the public debate in Brazil as the financing of politics, particularly political parties. This will be one of the central subjects for our next event, next week.

On Thursday, May 10th, at 10 am, Dr. Udo Di Fabio, a professor at University of Bonn and a former judge on the German Constitutional Court will give a lecture, followed by a debate, titled Political Parties: Constitutional Status, Financing and New Challenges. Everyone is welcome to attend.

On Thursday, April 26, at 10am, our International Dialogues in Constitutional Law is back, with Professor Prof. Dr. Francisco J. Urbina (Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile).

He will talk about his book A Critique of Balancing and Proportionality. Urbina is one of the main critics of balacing and proportionality as methods for settling disputes and applying the law. His 2017 book is unquestionably a major contribution in the topic.

Urbina will also join us in a closed-doors seminar on April 27, also at 10am, when we will discuss his working paper “Separation of powers: the minimal view”. RSVP required via email: dialogues@usp.br.

In the second meeting of the International Dialogues in Constitutional Law series in 2017, held on May 17, Anthony Pereira (King’s College London) presented his lecture entitled Progress or Perdition? Brazil’s National Truth Commission in Comparative Perspective.

Pereira presented the main reasons that led him to write about transitional justice in Brazil. In particular, he focused on two reasons: the first is that transitional justice in Brazil began long after the key events of the authoritarian period, especially if compared to other Latin American countries; and, second, the apparent inaccuracy of the official data on violence during the authoritarian period: unlike the case in other Latin American countries, the data shows that violence is much higher now than during the authoritarian regime.

Pereira also discussed the lessons he learned after analyzing the transitional justice in Brazil. He argued that in order to effectively understand the results produced by the Truth Commission, it is necessary to fully understand its institutional context. Moreover, he argued that transitional justice should be analyzed from an interdisciplinary perspective, not only from the perspective of the social sciences, but also from a normative and ethical perspective.

In the first meeting of the International Dialogues in Constitutional Law series in 2017, on April 19, our guest was Roberto Gargarella, from the University of Buenos Aires (UBA).

In his lecture, Gargarella presented the reasons why, in his view, the new Latin American constitutionalism has not been able to respond effectively to contemporary challenges.

According to Gargarella, the main function of constitutionalism is to cope with the dramas of its time. The first constitutions of Latin America attempted to respond to the question of how to organize power.

The contemporary Latin American constitutions face a distinct challenge: the massive violations of human rights by the Latin American states. To this end, the adopted strategy has been the accumulation of declarations of rights, many of them with conflicting goals: classical liberal rights, social rights, transindividual rights and rights provided for in international human rights treaties.

One major problem with this strategy lies in the fact that it does not affect power structures, and this undermines the enforcement of rights.

Our International Dialogues in Constitutional Law series starts off 2017 with Roberto Gargarella (Univ. de Buenos Aires). Tomorrow, we host Professor Gargarella for his lecture “Too much ‘old’ in the ‘new’ Latin American constitutionalism?”. Earlier today, he joined us for a discussion on his working paper about dialogic constitutionalism.

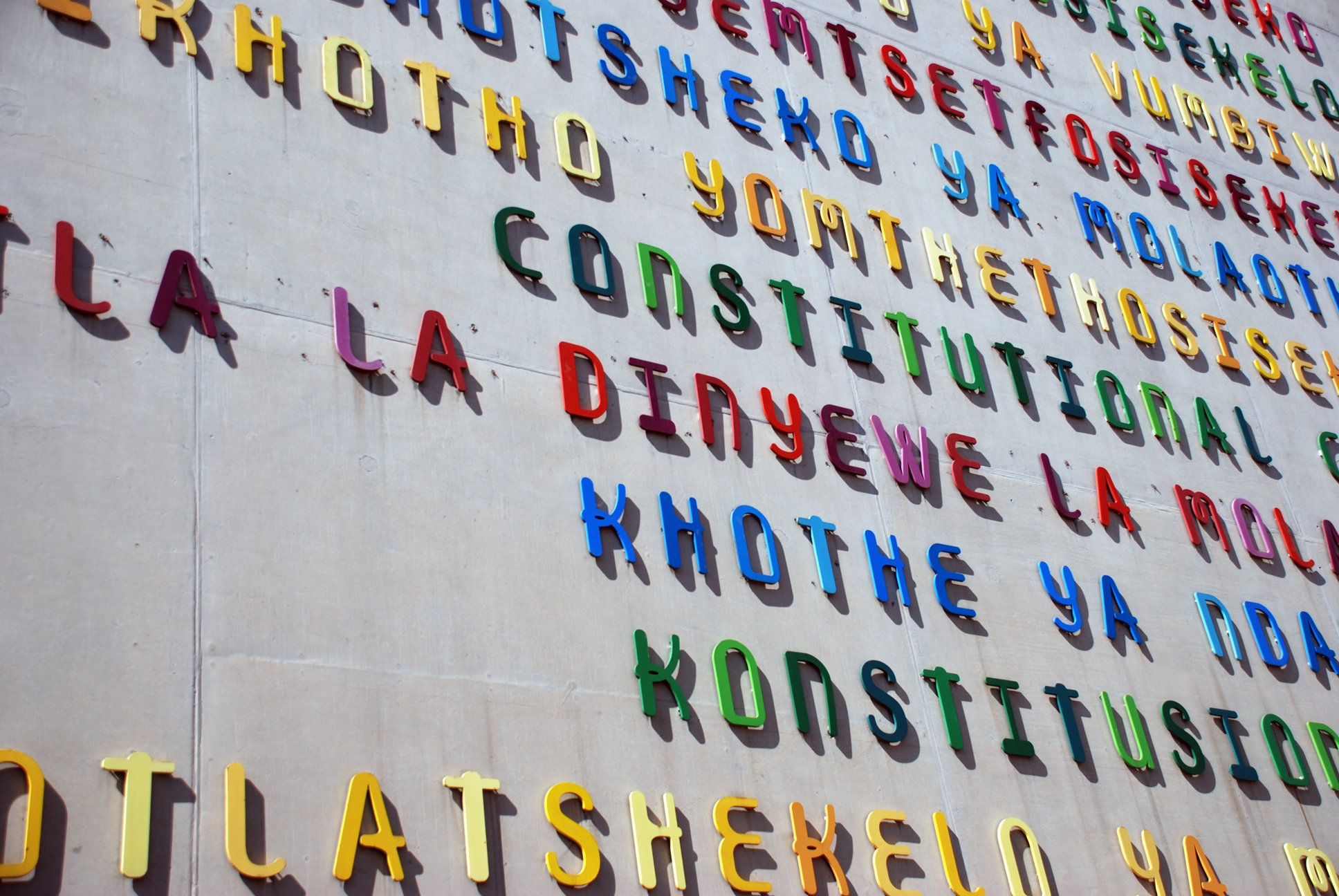

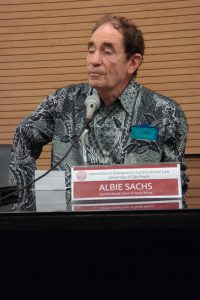

On November 3, 2016, Albie Sachs, former judge of the Constitutional Court of South Africa, held the closing lecture of the International Dialogues in Constitutional Law series in 2016. After his lecture, there was also a signing session of the Brazilian edition of Sachs’ autobiographical book, The Strange Alchemy of Life and Law (translated into Portuguese by Saul Tourinho Leal).

Following the narrative of his book, in his lecture Sachs referred to personal events, both as a judge of the Constitutional Court and as a political activist in defense of public liberties.

According to Sachs, an important function of a constitution is to ensure the coexistence of groups with different ideologies, religions, sexual orientation etc. He argued that, for this to happen, it is necessary to promote equality in the recognition of rights. Sachs presented his role in the decision of the Fourie case on same-sex marriage in South Africa. He also addressed the issue of political reconciliation in South Africa in the post-apartheid period, also through a personal narrative involving the perpetrator of the attack he had been a victim while still in exile in Mozambique.

The participation of Albie Sachs in our series of debates was supported by Saul Tourinho Leal and the AJD – Judges for Democracy Association.

Our International Dialogues on Constitutional Law hosted Ralf Poscher (Universität Freiburg). He talked about freedom of assembly, drawing from his experience in devising a ‘master code’ for freedom of assembly in Germany.

Poscher started his talk by emphasising what he thinks is the central aspect of the freedom of assembly, the physical presence of demonstrators, who ‘stand with their bodies’ for the ideas they advocate, he said. This makes protests a special kind of expression, different from writing an op-ed piece for a newspaper, for instance. It is precisely because a demonstrator’s body is exposed that he is afforded the special protection of the freedom of assembly.

Regulation must have this aspect above all, Poscher argued: while some restrictions required to prevent harm should be admitted, those are second-level concerns. The primary goal of regulation should be to “enable and facilitate the exercise of the right of assembly”.

Law should then respect the autonomy of the assembly: organisers should be free to pick the purpose, the time, the route and generally how to organise it. The master code consequently admits assemblies that have no leaders or formal organisation even, although it does provide for a kind of assembly which is directed by a leader, who is given power to take decisions which are legally binding upon demonstrators. The police, in that case, are only allowed to interfere with the assembly after calling upon the leader of the assembly to address an issue (by removing a demonstrator engaging in disorderly conduct, for instance) by themselves.

The master code also includes a mandante that organisers give the police 48h notice of the assembly, or face a misdemeanour charge. This is mitigated for spontaneous assemblies and assemblies called with less than 48h before the time of the assembly.

The police are only allowed to interfere with the assembly when there is a ‘imminent, concrete risk to public safety’, Poscher explained. This means that abstract speculations and even concrete risk of minor illegal behaviour do not sanction police interference. And the police are only allowed to disband an assembly when it deems there is no alternative to preventing harm. Only following this formal decision by the police, and after demonstrators are warned and given appropriate notice, are then the police allowed the proceed under ‘regular police law’.

Demonstrators are also generally entitled to wear masks and protective gear. Those might be needed so that individuals are able to exercise their freedom of assembly, wearing masks to avoid retaliation for joining a protest, and protective gear to protect against those who would explore their bodily exposition to harm them. Conceding that those may also be use to facilitate illegal conduct, the master code provides that the police may order demonstrators to remove those, again in a formal decision which may be challenged in court afterwards.

Similar rules apply to assemblies in privately-held public places: if those are used for transit as streets and parks are, demonstrators are not required to secure consent of the owner.

Poscher finally highlighted that while those provisions are all important in preserving freedom of assembly, a democratic culture in policing is just as important; police, he insisted, must have a clear view of their professional responsibility to enable and facilitate assemblies, instead of limiting or managing them.

On September 28, Daniel Bonilla, professor at the Los Andes University (Colombia), was the guest of the seventh meeting of the International Dialogues in Constitutional Law in 2016. In his lecture, entitled Constitutionalism in the Global South, Bonilla presented some of the ideas of the influential book he edited, Constitutionalism of the Global South: The Activist Tribunals of India, South Africa and Colombia (Cambridge University Press).

His arguments challenge both the way the legal scholarship of the Global North takes (or does not take) into account what is written by authors of the Global South, and the way how academics of the Global South itself sometimes uncritically absorb what is published in the North. Combining epistemological critique with political reflection, his reasoning unveils the power structures that normalize the dynamics of how we think about constitutional law and law as a whole. His ideas allow us to rethink how we conduct research in constitutional law, challenging whether the mainstream canons of the North are really suited to deal with the challenges peculiar to the Global South.